Textual Criticism and the Bible

In our scientific and educated age we question many of the non-scientific beliefs that earlier generations had. This skepticism is especially true of the Bible. Many of us question the reliability of the Bible from what we know about it. After all, the Bible was written more than two thousand years ago. But for most of these millennia there has been no printing press, photocopy machines or publishing companies. So the original manuscripts were copied by hand, generation after generation. Concurrently, languages died out and new ones arose, empires changed and new powers ascended.

Since the original manuscripts have long been lost, how do we know that what we read today in the Bible is what the original authors actually wrote? Perhaps the Bible was changed or corrupted. Maybe church leaders, priests, bishops, or monks did so because they wished to change its message for their purposes.

Principles of Textual Criticism

Naturally, this question is true of any ancient writing. Textual Criticism is the academic discipline determining whether an ancient text has changed from its original composition until today. Because it is an academic discipline it applies to any ancient writing from any language. This article explains some basic principles of Textual Criticism and applies them to the Bible to determine its reliability.

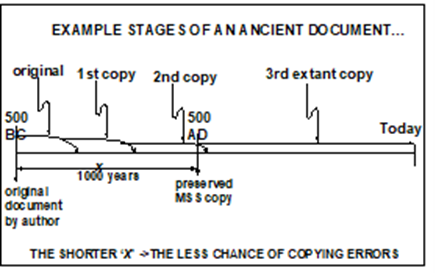

This diagram shows an example of a hypothetical document written 500 BCE. The original text did not last long. So before it decays, is lost, or destroyed, a manuscript (MSS) copy of it must be made (1st copy). A professional class of people called scribes did the copying. As the years advance, scribes make copies (2nd & 3rd copy) of the 1st copy. At some point a copy is preserved so that it exists today (the 3rd copy).

Principle 1: Manuscript Time Intervals

In our example diagram scribes produced this extant copy in 500 CE. So this means that the earliest that we can know of the state of the text is only after 500 CE. Therefore the time from 500 BCE to 500 CE (labeled x in the diagram) forms the period of textual uncertainty. Even though the original was written long before, all manuscripts before 500 CE have vanished. Therefore we cannot evaluate copies from this period.

Thus, the first principle used in textual criticism is to measure this time interval. The shorter this interval x the more confidence we can place in the correct preservation of the document to our time, since the period of uncertainty is reduced.

Principle 2: The number of existing manuscripts

The second principle used in Textual criticism is to count the number of existing manuscripts today. Our example illustration above showed only one manuscript available (the 3rd copy). But usually more than one manuscript copy exists today. The more manuscripts in existence in the present day then the better the manuscript data. Then historians can compare copies against other copies to see if and how much these copies deviate from each other. So the number of manuscript copies available becomes the second indicator determining the textual reliability of ancient writings.

Textual Criticism of Classical Greco-Roman writings compared to Brit Chadasha

These principles apply to any ancient writings. So let us now compare Brit Chadasha manuscripts with other ancient manuscripts that scholars accept as reliable. Here we do the same with the Tanakh. This Table lists some well-known ones…

| Author | When Written | Earliest Copy | Time Span | # |

| Caesar | 50 BCE | 900 CE | 950 | 10 |

| Plato | 350 BCE | 900 CE | 1250 | 7 |

| Aristotle* | 300 BCE | 1100 CE | 1400 | 5 |

| Thucydides | 400 BCE | 900 CE | 1300 | 8 |

| Herodotus | 400 BCE | 900 CE | 1300 | 8 |

| Sophocles | 400 BCE | 1000 CE | 1400 | 100 |

| Tacitus | 100 CE | 1100 CE | 1000 | 20 |

| Pliny | 100 CE | 850 CE | 750 | 7 |

McDowell, J. Evidence That Demands a Verdict. 1979. p. 42-48

* from any one work

These writers represent the major classical writers of antiquity. Basically, their writings shaped the development of European and Western civilization. But on average, they have been passed down to us by only 10-100 manuscripts. Moreover, the earliest existing copies are preserved starting about 1000 years after the original was written. We treat these as our control experiment since they comprise writings that form the foundation of history and philosophy. So academics and universities world-wide accept, use and teach them.

Brit Chadasah Manuscripts

The following table compares the Brit Chadasha manuscripts along the same principles of Textual Criticism. Then we will compare this to our control data, just like in any scientific investigation.

| MSS | When Written | Date of MSS | Time Span |

| John Rylan | 90 CE | 130 CE | 40 yrs |

| Bodmer Papyrus | 90 CE | 150-200 CE | 110 yrs |

| Chester Beatty | 50-60 CE | 200 CE | 20 yrs |

| Codex Vaticanus | 50-90 CE | 325 CE | 265 yrs |

| Codex Sinaiticus | 50-90 CE | 350 CE | 290 yrs |

Comfort, P.W. The Origin of the Bible, 1992. p. 193

However, this table gives just a brief highlight of some of the existing Brit Chadasha manuscripts. The number of Brit Chadasha manuscripts is so vast that it would be impossible to list them in a table.

Testimony of the Scholarship

As one scholar who spent years studying this issue states:

“We have more than 24000 MSS copies of portions of the New Testament in existence today… No other document of antiquity even begins to approach such numbers and attestation. In comparison, the ILIAD by Homer is second with 643 MSS that still survive”

McDowell, J. Evidence That Demands a Verdict. 1979. p. 40

A leading scholar at the British Museum corroborates this:

“Scholars are satisfied that they possess substantially the true text of the principal Greek and Roman writers … yet our knowledge of their writings depends on a mere handful of MSS whereas the MSS of the N.T. are counted by … thousands”

Kenyon, F.G. (former director of British Museum) Our Bible and the Ancient Manuscripts. 1941 p.23

This data pertains specifically to the Brit Chadasha manuscripts. This article looks at Textual Criticism of the Tanakh.

Brit Chadasha Textual Criticism and Constantine

Significantly, a large number of these manuscripts are extremely ancient. For example, consider the introduction of the book transcribing the earliest Greek Brit Chadasha documents.

“This book provides transcriptions of 69 of the earliest New Testament manuscripts…dated from early 2nd century to beginning of the 4th (100-300AD) … containing about 2/3 of the new Testament text”

Comfort, P.W. “The Text of the Earliest New Testament Greek Manuscripts”. p. 17. 2001

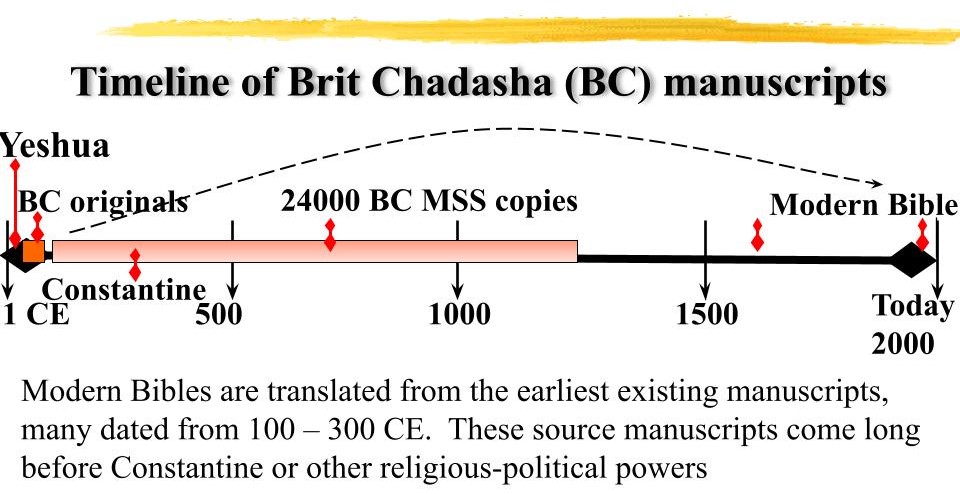

This is significant because these manuscripts come before Roman Emperor Constantine (ca 325 CE). They also precede the rise to power of the Catholic Church. Some wonder whether either Constantine or the Catholic Church altered the Brit Chadasha text. We can actually test this by comparing the manuscripts from before Constantine (325 CE) with those coming later. However, we find that they have not changed. The manuscripts from, say 200 CE, are the same as those that come later.

Thus, neither the Catholic Church, nor Constantine changed the Brit Chadasha . This is not a religious statement, but based solely on the manuscript data. The figure below illustrates the timeline of manuscripts from which today’s Brit Chadasha comes from.

Implications of Bible Textual Criticism

So what can we conclude from this? Certainly, at least in what we can objectively measure, the Brit Chadasha is verified to a much higher degree than any other classical work. The verdict can be best summed up by the following:

“To be skeptical of the resultant text of the New Testament is to allow all of classical antiquity to slip into obscurity, for no other documents of the ancient period are as well attested bibliographically as the New Testament”

Montgomery, History and Christianity. 1971. p.29

What he means is that if we doubt the reliability of the Bible’s preservation we should discard all that we know about classical history. Yet no informed historian has ever done so. We know that the Biblical texts have not been altered as eras, languages and empires have come and gone. We know this because the earliest existing manuscripts precede these events. For example, we know that no overly zealous medieval monk, or plotting pope, added in the miracles of Yeshua to the Brit Chadasha. We have manuscripts that come before all medieval monks and popes. Since all these early manuscripts contain Yeshua’s miracles then these imaginary medieval conspirators could not have inserted them.

What about translation of the Bible?

But what about the errors involved in translation? Why are there so many different versions of the Bible today? Do the many version show that it is impossible to accurately determine what the original authors actually wrote?

First, let us clear up a common misconception. Many think that the Bible today has gone through a long series of translation steps. They imagine each new language translated from the previous one. So they visualize a series something like this: Greek -> Latin -> Medieval English -> Shakespeare English -> modern English -> other modern languages.

In fact, linguists translate the Bible into the diverse languages today directly from its original languages. So for the Brit Chadasha the translation proceeds Greek -> modern language. For the Tanakh the translation proceeds Hebrew -> another language (further details here). But the base Greek and Hebrew text is standard. So the different Bible versions comes from how linguists choose to translate into the modern language.

Translation Reliability

Due to the vast classical literature that was written in Greek (original language of the Brit Chadasha), it is possible to precisely translate the original thoughts and words of the original authors. In fact, the different modern versions attest to this. For example, read this well-known verse in the most common versions, and note the slight variance in wording, but consistency in idea and meaning:

For the wages of sin is death, but the gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.

Romans 6:23 (New International Version)

For the wages of sin is death, but the gracious gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.

Romans 6:23 (New American Standard Version)

For the wages of sin is death, but the gracious gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.

Romans 6:23 (New Living Translation)

You can see that there is no disagreement between the translations because they say exactly the same thing using only slightly different words.

Conclusion

To summarize, neither time nor translation has corrupted the ideas and thoughts expressed in the original Bible manuscripts. These ideas are not hidden from us today. We know that the Bible today accurately communicates what its authors actually wrote back then.

But it is important to realize what this study does not show. This does not necessarily prove that the Bible is the Word of G-d.

But understanding the textual reliability of the Bible provides a start-point from which we can start investigating the Bible. We can see if these other questions can also be answered. We can also become informed about its message. Since the Bible claims that its message is G-d’s blessing to you what if it is possibly true? Perhaps it is worth taking the time to learn some of the important events of the Bible. A good place to start is in its beginning.

1. McDowell, J. Evidence That Demands a Verdict. 1979. p. 42-48

2. Comfort, P.W. The Origin of the Bible, 1992. p. 193